REVEALING A HIDDEN LEGACY: THE STORY OF THE TAYLOR ESTATE

University of Houston students bring the rich history of the Taylor Estate to life through art and collaboration

This semester, students from the University of Houston had the unique opportunity to collaborate on an exhibit that brings the history of the Taylor Estate to life. Senior graphic design students from the Kathrine G. McGovern College of the Arts' School of Art and fourth and fifth-year architecture students from the College of Architecture and Design worked together to create installations that highlight the land’s rich legacy, exploring themes of love, struggle, land, and oil. Their collective effort offers a fresh, engaging perspective on a story that has spanned over seven generations.

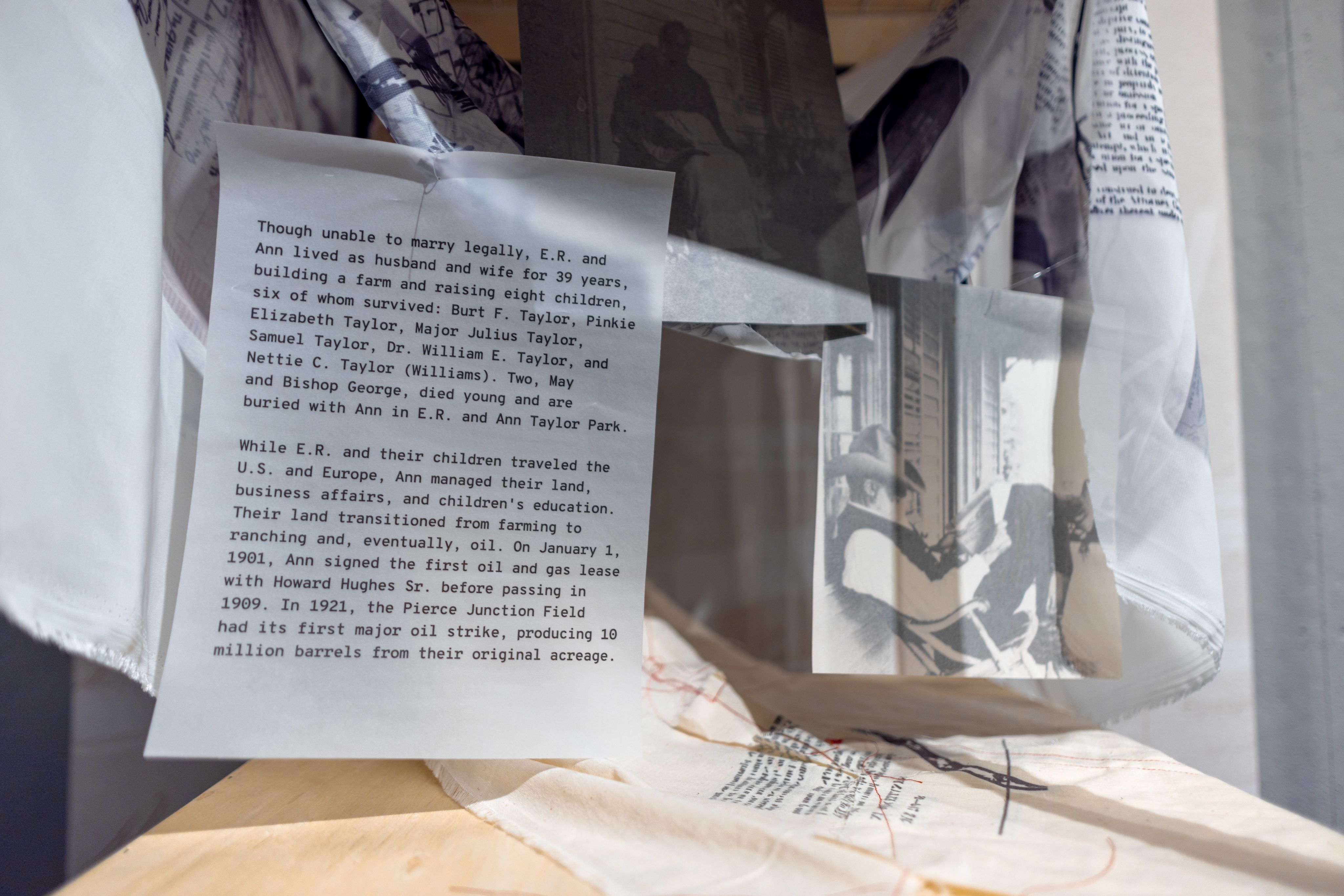

Beverly Stevenson, Ph.D., a renowned leader in both the business and community sectors, uncovered a hidden and long-suppressed story from the Civil War era. It centered on the forbidden relationship between Edward Ruthven Taylor, the white son of a well-known Texas slave trader, and Ann George, a Black woman enslaved by his family.

This poignant tale came to light through the great-grandson of the couple, Major William Stevenson Sr., whom Dr. Stevenson was dating at the time and would later marry.

When Dr. Beverly Stevenson first learned the story of Edward Ruthven Taylor and Ann George, she was captivated. The interracial couple lived their lives largely in obscurity, but their 640-acre homestead turned out to be rich in oil and minerals. Over 152 years, their business has sustained seven generations. Edward and Ann, who had six children of mixed race, were among the first African Americans in Texas to attend college and earn degrees in the 1890s.

The couple's story sparked deep reflection in Stevenson, challenging her views on race, class, identity, and social hierarchy. Driven by a need to understand, she dedicated 25 years alongside her husband to carefully studying letters, receipts, ledgers, wills, and countless other documents passed down over the generations. Their journey became an urgent pursuit for her—one that not only uncovered layers of American history but also shed light on the enduring legacy of slavery and the complexities of race relations in today’s world.

In the early 2000s, a significant connection was forged between Beverly Stevenson and the University of Houston when architecture professor Susan Rogers, along with a group of students in the Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF), visited the Taylor Estate.

Rogers was immediately captivated by the site, feeling a profound inspiration that would deepen and evolve over the years.

Last summer, that initial spark of inspiration was reignited when Stevenson reached out to Rogers once again. Eager to revisit the conversations they’d had years earlier, Stevenson invited Rogers to meet and discuss the next steps. During their meeting, Rogers shared that she and her colleague, Cheryl Beckett, associate professor of graphic design, had recently completed an exterior installation project for the Friends of Columbia Tap on the Columbia Tap Trail. Stevenson, excited by the idea of telling the Taylor Estate’s story through installation art and student involvement, saw an opportunity to celebrate the estate's history in a new way.

The project truly took shape when Rogers, Beckett, and 38 students gathered at Stevenson’s home. There, Stevenson shared the stories passed down over the years, breathing new life into the land’s rich legacy for the students. With deep ties to the University of Houston, where she had worked for years and where her late husband had also studied, Stevenson held a profound respect for the institution. It was clear that this partnership, years in the making, had come full circle. To bring this exhibit to life, Cheryl Beckett received the Cynthia Woods Mitchell Center for the Arts Innovation Grant.

Telling someone else’s story, especially through art or design, is never an easy task. As Cheryl Beckett explains, one of the challenges was finding a way to tell the story accurately while selecting the right approach. "The first step was deciding how we would tell this story,” she says. "Last year, when Susan and I worked together on the Friends of Columbia Tap project, we were outdoors at the actual site. But for this project, that would have been an incredibly difficult, if not impossible, challenge." Instead, they decided that an interior exhibition would be a more effective way to share the story with a wider audience, providing a more focused and accessible way to convey the history they aimed to honor.

"Cheryl and I established the conceptual framework for the project, using the 'over/under' theme," said Rogers. "We wanted to explore what was above the land—things like the family, the oil, the generations—and what lay beneath, such as the salt dome and the Pierce Junction oil field where gas is now stored." This framework allowed the teams to delve into the layered history of the land, balancing its surface-level stories with deeper, often hidden narratives.

The graphic design students encountered a range of challenges while collaborating on the exhibit, particularly when transitioning from flat design to a three-dimensional space. Violetta Terekhina remarked, "We primarily work with flat, print design, so seeing it in a 3D space and figuring out how to make that work was challenging, but also exciting."

Violetta Terekhina

Violetta Terekhina

Vanessa Bravo found working alongside an architect student to be a unique experience, given their differing approaches. "We think very differently. Our architect was focused on function, while I was more concerned with expressing the idea through form," she explained.

Vanessa Bravo

Vanessa Bravo

Madison Galvez described the difficulty of transforming abstract concepts into tangible results. "Initially, we tend to think abstractly, but with the help of the team, we created something that felt both real and feasible."

Madison Galvez

Madison Galvez

The students unanimously agreed that the most rewarding aspect was witnessing their work come to life. Terekhina said, "It was exciting to see everything come together, especially after making last-minute adjustments." Galvez echoed this sentiment, stating, "The installation was incredibly rewarding. It felt great seeing it align with our original vision."

As the exhibit's opening approached, the students were eager to see how visitors would react. Galvez looked forward to seeing how people would engage with the installation, while Bravo was excited about the family's response. "I think they're going to be blown away," she said.

The process of telling someone else’s story artistically was no small feat, but the students rose to the challenge. As Beckett observed, "It’s really impressive how quickly everything came together. These students worked incredibly hard, and I think they did a great job balancing artistic expression with the need to accurately convey the history."

The exhibit will be on view from March 20 to April 25, Monday through Friday, from 9:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. It is in the Community Design Resource Center (CDRC) adjacent to the Atrium on the ground floor of the College of Architecture & Design, Room 102, at 4200 Elgin St., Houston, TX 77204.