HOUSTON STREET ARTIST GONZO247 EXPLORES PANDEMIC'S IMPACT ON CITY THROUGH GRAFFITI

Inspired by community responses, the artist’s series is now on exhibition at the Blaffer Art Museum

Growing up in Houston’s Eastwood neighborhood, Mario E. Figueroa, Jr.—better known by the moniker GONZO247—wasn’t exposed to much art. But a lone mural near his home served as a beacon, guiding him toward what would ultimately become his life’s vocation.

“In those years, there really wasn't much public art in the city, especially in my neighborhood,” Figueroa said. “But there was one mural on Canal Street. And that one mural was the only art I had access to. It was on the street. And really that mural inspired me to want to grow up to be an artist.”

While that mural may have instilled in Figueroa the desire to create, it wasn’t until the arrival of hip-hop culture, and graffiti with it, that he realized there was an outlet for his artistic inclinations.

“It wasn't until 1979-1980 when I first heard this new thing called rap music,” Figueroa said. “And then when I saw graffiti, I was like, ‘Yo, what is this?’.”

“Graffiti is the visual language of hip-hop and, already being artistically inclined, that's the first time I saw a form of creative expression that I could connect with directly,” Figueroa said.

Figueroa's career began in the early days of graffiti, when cities themselves became canvases for kids forging a new interpretation of what art can be. Now commonly referred to as “street art,” graffiti is ubiquitous and has become a crucial part of our larger cultural narrative.

“It's the first American art movement that was born in America, that was made by kids, for kids,” Figueroa said.

“But to see where it's gone, now it has this global impact,” Figueroa said. “It evolved from just the kid jumping a fence illegally to paint a masterpiece at night to being sold at auctions for millions of dollars.”

Presently, the Blaffer Art Museum at the University of Houston is displaying an exhibition of some of Figueroa’s recent work—a series inspired by and reflective of the experiences of various Houstonians during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The works were produced in collaboration with Come Together Houston, a performance series funded by the CDC Foundation to provide information on the COVID-19 vaccine and its impact on the Houston community.

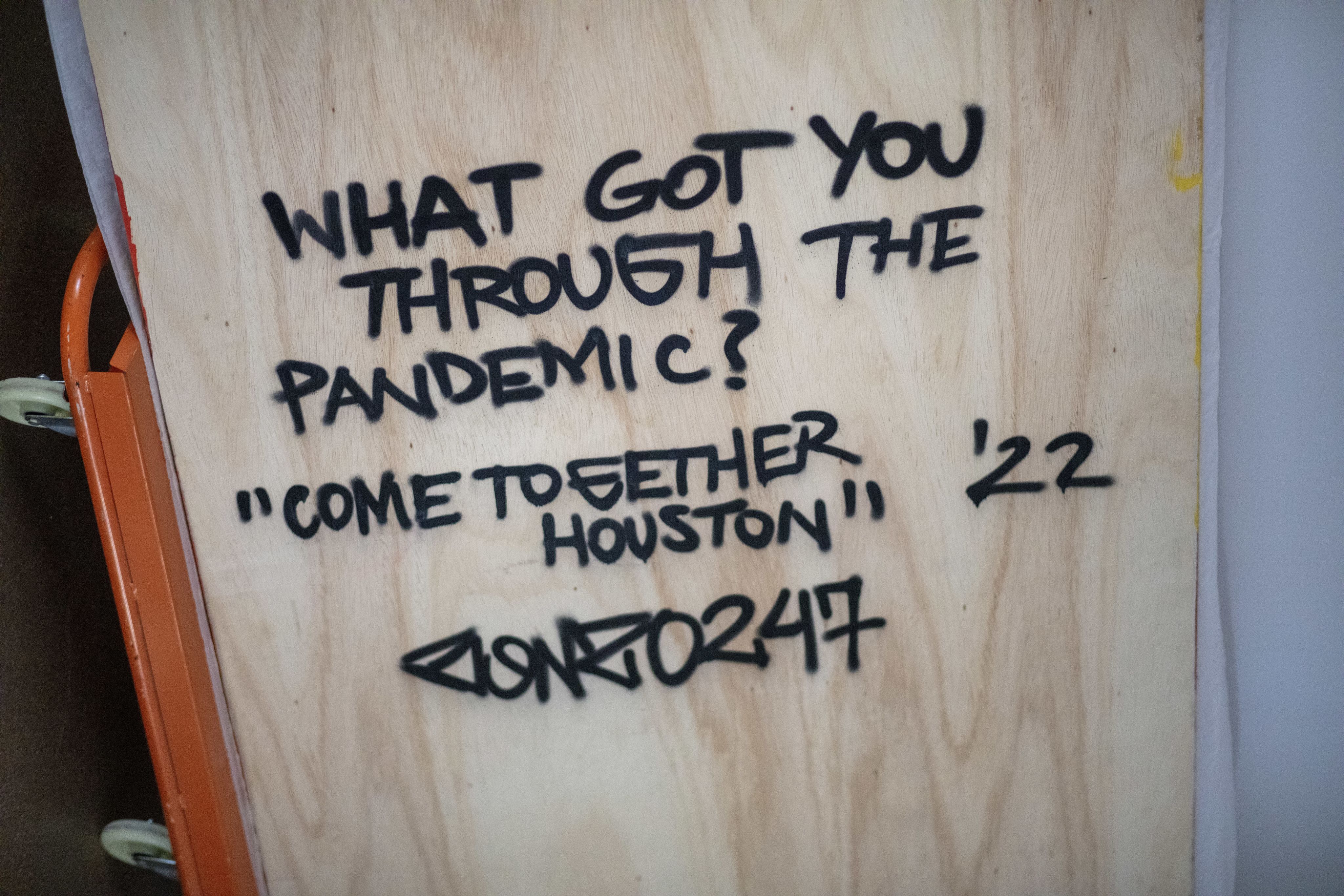

At multiple community events sponsored by Come Together Houston, Figueroa asked attendees, “What got you through the pandemic?” and “What are you looking forward to when the pandemic is over?”

Figueroa said he encouraged one-word responses.

“I had a little clipboard and everyone just gave me their one-word answer,” Figueroa said. “And then I started to collage these words in graffiti tag styles on the panel.”

The collages incorporated a variety of different visual elements, something Figueroa said was deliberate.

“Back in the day, you would go and you'd see this wall and it'd be all full of tags and they're all different colors, different styles. And you could see it's one whole thing, but, but you'd know that they're all individual voices on this wall.”

“So I wanted to do the same thing where we had all these different words and each word pretty much represented a different person and their perspective,” Figueroa said.

The resulting panels—three for each prompt response—now hang in the Blaffer. Figueroa said he sees some commonalities in the responses incorporated into the pieces, as well as some interesting differences.

“We’re all people, we're all human, but we all went through the pandemic differently,” Figeuroa said. “We all had the same thing to deal with, but we all had different ways of dealing with it.”

He said he attributes these differences to the differing socioeconomic statuses of the neighborhoods in which the events were held.

We had some words like ‘hope,’ ‘church,’—there are some words that you could really tell as a community overall, there's certain things that transcend neighborhoods,” Figueroa said. “And then of course some neighborhoods either were not as financially well off or didn't have the right medical care or access to certain infrastructure so that they went through it differently.”

Figueroa said both the creation of the panels and now their exhibition was an incredibly rewarding process. One he hopes viewers will appreciate.

“As people signed up the word, I would add it to it. So it was kind of like a visual performance,” Figueroa said.

“And what's cool is now that they're in this setting, you can still feel the energy of it. You can still see and feel the grit.”

“We’re all people, we're all human, but we all went through the pandemic differently,”

“We all had the same thing to deal with, but we all had different ways of dealing with it.”