AWARD-WINNING DIRECTOR JOSÉ ZAYAS BRINGS "MARISOL" TO UH

ZAYAS SITS DOWN WITH STAGE MANAGEMENT STUDENT JOSEPH BLANCHARD TO DISCUSS HIS LIFE AND WORK

Every seat in the Quintero Theatre is filled. People are chatting, reading playbills, and analyzing the giant tarp that is separating the audience from the rest of the room.

We notice the room is getting louder and louder, and the lights begin to flicker. Phones are going on silent, candy wrappers are being opened, and the room is suddenly black.

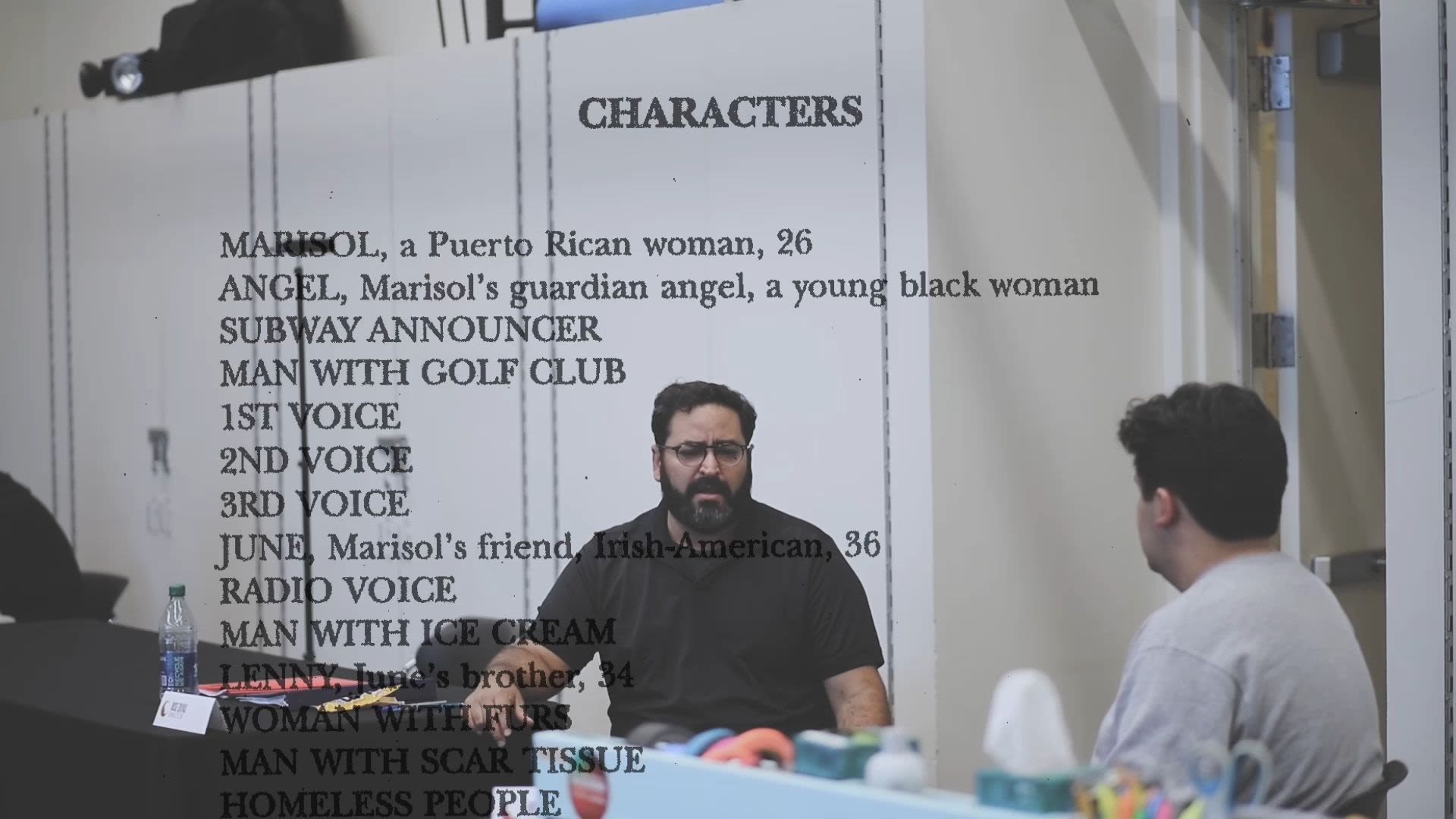

We are transported into the world of "MARISOL", the Obie award winning play by José Rivera. The world is large, gloomy, intense. Colors are bleeding together to create painting-like pictures on stage. It is loud, it is dark, and suddenly it is snowing. We’re five minutes in and there’s a lot going on. This is exactly how director José Zayas, self-proclaimed maximalist, envisioned it.

José Zayas is an award-winning director, with over 100 productions in New York, regionally, and internationally.

A few weeks ago I sat down to speak with Zayas about his work, his life, and how he manages to make it all happen.

Zayas comes to the University of Houston days after opening Fandangos for Butterflies (and Coyotes) with En Garde Arts at La Jolla Playhouse, the professional theatre at the University of California, San Diego.

Q&A with José Zayas, Director and Joesph Blanchard, Stage Manager of "MARISOL"

José: [My last project] was a show I was doing with on En Garde Arts in New York when COVID hit. It was gonna travel through all the boroughs. It's a piece that we worked on for two years. We interviewed nine undocumented immigrants in the city or right outside the city. And then we created a piece using Fandango language, vocabulary, music, to tell the story of these nine. It’s about how they tell each other's stories, how they sing. It's more a celebration of their lives. COVID cut it short. We had a video of it. We showed it to La Jolla, Chris Ashley loved it, said, I want to produce it when we come back. And that's what just happened. One of the first shows to come back.

Joseph: That's a super collaborative process.

José: Absolutely. Yeah.

Joseph: So now you are here working with a college team. Why do you like working at universities so much?

José: ...I mean, in a perfect world I do like four or five university gigs a year. That’s how much I like it... So usually, it's stuff that I really want to experience and be part of. I love working with students. I love that openness, malleability. I get to experiment more, and I get to play without the stress of, you know, it being reviewed or being in production.

Joseph: José Rivera mentioned that he wrote "MARISOL" with an eye on the next generation. What are you looking for college audiences to take from the show?

José: Obviously I think all of the issues and the themes are resonating with us even more so today. I mean, we are having much more human conversations and much more heated conversations about things like climate change, about the possibilities of how the world is shifting around us. I think the idea, like looking at a character whose identity has been shaped by denial, and as [Marisol] said, exercised certain elements of [her] life in order to pass. I think these conversations are much more explicit than they were when he wrote it.

I think these characters exist more in our culture visibly than they did. So I just want people to be able to like, look at what Marisol is and we sort of look at how psychologically the person who she had to be or who she forces her to become is ultimately affecting the world that surrounds her. I mean, I think that they're all linked poetically and hopefully they'll see that connection and sort of the immediacy of that will be something that's starting conversations.

Joseph: Do you think magical realism, the genre of the show, is a more effective way than others to reach a collegiate audience?

José: I think this is fantasy to me. People will define it as some... marketing elements of magic realism. And it's tricky for me. Cause I think magic realism has to be our present or our reality. This is already starting in a world that's heightened, it's already a fantasy world. The moon is not there, coffee is extinct. Um, it's already happening in a different timeline. To me magic realism is in our timeline and then odd things occur inside that.

So it's usually magic realism to me is like, it's smaller. The gestures are more delicate. Here, men are pregnant and give birth. There's like huge cosmic events. Angels are real. So to me it's more fantasy and sci-fi.

Joseph: Interesting. Why is that exciting to you? You do like horror movies too, that's your big thing.

José: Oh man. I love genre. I love horror. I love any genre piece. I mean, I don't get to do movies, unfortunately. I wish I could do movies. Eventually I will. But I just love the possibilities, the visual possibilities, the emotional richness that genre allows you, that you don't have to deal in the literal, I don’t really like the literal. But I do it. And I've been known to do it well, but I like the poetry that this kind of material allows you.

Joseph: We’ve been using the word cinematic a lot on this show. And that's not something that I hear a lot during process. How do you think the cinematic approach helps the story move along?

José: I think there's just a lot of... writers, modern writers, think cinematically. So cinematic to me is moving quickly through scenes. I think short scenes moving in very dramatic or dynamic shifts in time and place. Scenes that are mostly like, “Oh, it's a silent section and we're just gonna watch Marisol dress.” That to me is a very cinematic gesture. So when we have like long sequences of silence or these very quick scene changes in time and location, I find them cinematic. I find a lot of the way that I have to solve this, I have to have a cinematic mind to make it click.

Joseph: I can see how that would be interesting to college designers, right? That’s very different than like, the Molière piece we’re doing downstairs. (The Learned Ladies)

José: Yeah, it’s very different. But it is what's happening in the theatrical language. I mean, when you're in school you're doing these works, but you're not gonna be doing Molière that much out there for the most part. I think especially in New York, and because I work a lot in new plays, most new plays are like this. Most plays are thinking like movies. For better or worse, some people really love it, some people really hate it and they think it's a lesser form of theater making... I just think it's here and that's what you do.

"MARISOL" by José Rivera, directed by José Zayas runs October 21-30 in the Quintero Theatre at the School of Theatre and Dance.